Compressed Air Energy Storage: A Long-Duration Solution Evolving for a Renewable Power System

Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES) is one of the oldest grid-scale storage concepts—and it is getting a modern upgrade as the energy system shifts toward higher shares of wind and solar.

CAES is particularly relevant when the challenge is not minutes, but hours to multi-day balancing: absorbing surplus renewable electricity and delivering it back when demand is high or generation is low. Unlike most battery systems, CAES can be built for very large energy volumes—provided the right site and infrastructure are available.

CAES in One Paragraph

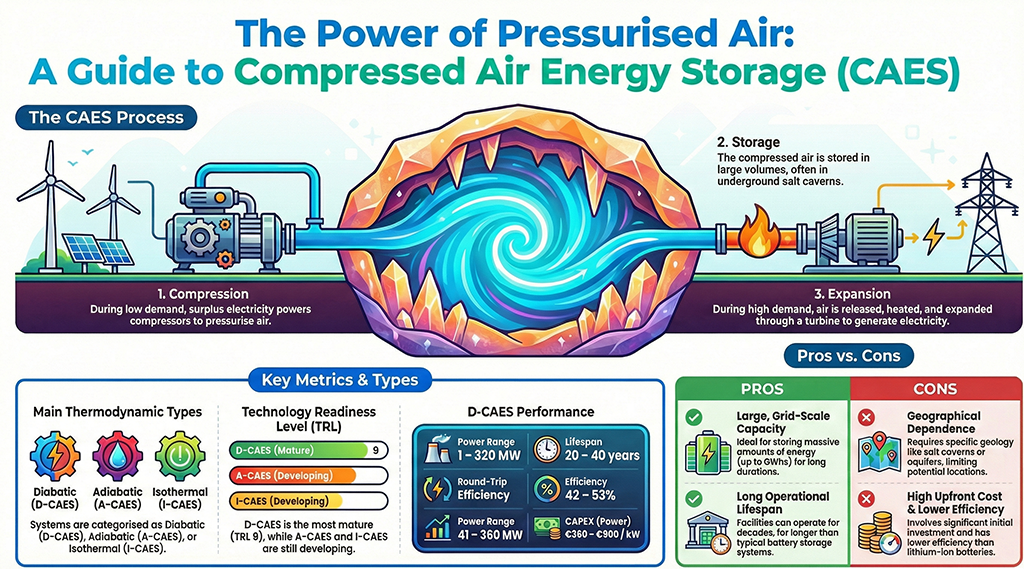

During low-demand periods, electricity powers compressors that pressurize air. The air is stored—typically in underground formations such as salt caverns, aquifers, or depleted gas fields (and, increasingly, in engineered vessels or subsea concepts). When power is needed, the compressed air is released, conditioned (heated and/or thermally managed), and expanded through turbines to generate electricity.

The Numbers at a Glance (Typical Ranges)

From the StoreMore Outlook analysis, CAES is commonly described by the following performance and cost ranges:

Energy density (volumetric): ~3–24 kWh/m³.

Power range: ~1–320 MW (project-dependent).

Energy retention / storage period: hours to weeks (low self-discharge).

Discharge duration: ~2 to 26 hours.

Lifetime: ~20–40 years (with no intrinsic “battery-like” degradation).

Round-trip efficiency (RTE): roughly 42–53% (diabatic), 52–60% (adiabatic), and up to ~83% (isothermal concepts).

Technology readiness (TRL): ~9 (diabatic CAES), ~7–8 (adiabatic), ~5–6 (isothermal concepts).

System scale: energy capacity can reach up to the GWh class.

Indicative CAPEX: ~360–900 EUR/kW (power) and ~2–225 EUR/kWh (energy), with indicative OPEX around ~8 EUR/kW-year.

A practical takeaway: CAES is most competitive when you need long life, long duration, and large scale—and when the storage site (or an engineered alternative) is feasible.

Three CAES Families You’ll Hear About

CAES is not a single technology—its performance depends heavily on how heat is handled during compression and expansion:

Diabatic CAES (D-CAES): compression heat is largely rejected; air is reheated before expansion (often with an external heat source). Mature, but lower efficiency.

Adiabatic CAES (A-CAES): captures and stores compression heat (thermal energy storage) and reuses it during discharge. Higher efficiency, less reliance on external heating, still scaling up.

Isothermal CAES (I-CAES): aims to compress/expand closer to constant temperature to reduce losses. Potentially very high efficiency, but technically challenging and earlier-stage.

Where CAES Adds the Most Value

CAES shines in grid and industrial roles where long duration and repeatability matter:

Renewable energy shifting: store excess wind/solar and deliver later to reduce curtailment.

Grid reliability services: peak shaving, reserve capacity, and resilience—especially for multi-hour events.

Industrial stability: sites with fluctuating loads can smooth demand and reduce peak electricity costs.

Backup and emergency supply: long-duration discharge supports critical infrastructure during outages.

What Holds CAES Back

CAES has clear trade-offs that must be addressed early in project development:

Site dependency: classic CAES needs suitable geology (salt caverns, aquifers, depleted gas fields).

Efficiency gap: conventional CAES can be materially less efficient than modern battery systems; advanced designs improve this but add complexity.

Capital intensity: large civil works, turbomachinery, and (for advanced systems) thermal storage can raise upfront investment needs.

Permitting and regulation: subsurface storage, land use, and environmental approvals can extend timelines.

From Classic Caverns to New Concepts

CAES has proven itself historically through cavern-based plants, but today’s innovation wave is trying to expand where CAES can be built and how efficient it can be.

Modern adiabatic systems focus on capturing compression heat and reusing it to boost efficiency.

Subsea and offshore concepts propose storing air in underwater structures or repurposing existing offshore infrastructure to reduce onshore constraints.

On-surface and modular approaches are being explored, but they tend to have lower maturity and more challenging economics at large scale.

The strategic direction is clear: widen the geographic feasibility beyond “perfect geology,” while pushing efficiency toward the upper end of long-duration storage options.

News & Events

Read the most recent updates and explore the upcoming events.